Introduction: Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Identify Linux filesystems.

- Identify the differences between partitions and filesystems.

- Describe the boot process.

- Install Linux on a computer.

The Boot Process

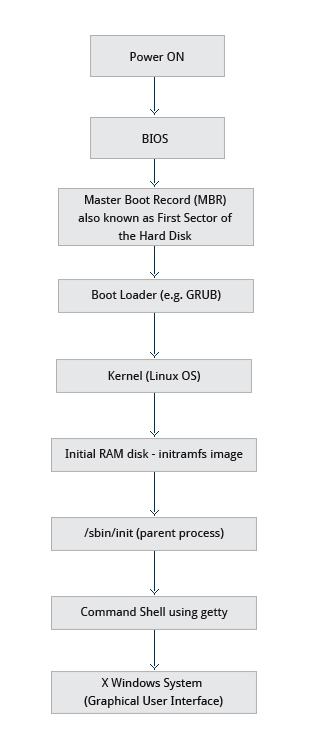

The Linux boot process is the procedure for initializing the system. It consists of everything that happens from when the computer power is first switched on until the user interface is fully operational.

Having a good understanding of the steps in the boot process may help you with troubleshooting problems, as well as with tailoring the computer’s performance to your needs.

On the other hand, the boot process can be rather technical, and you can start using Linux without knowing all the details.

NOTE: You may want to come back and study this section later, if you want to first get a good feel for how to use a Linux system.

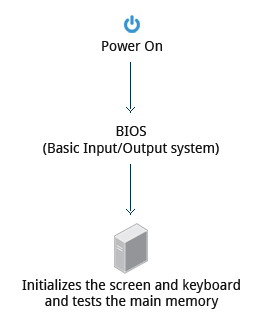

BIOS – The First Step

Starting an x86-based Linux system involves a number of steps. When the computer is powered on, the Basic Input/Output System (BIOS) initializes the hardware, including the screen and keyboard, and tests the main memory. This process is also called POST (Power On Self Test).

The BIOS software is stored on a ROM chip on the motherboard. After this, the remainder of the boot process is controlled by the operating system (OS).

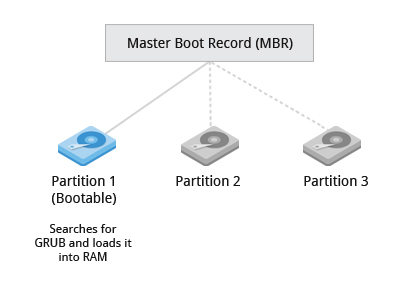

Master Boot Record (MBR) and Boot Loader

Once the POST is completed, the system control passes from the BIOS to the boot loader. The boot loader is usually stored on one of the hard disks in the system, either in the boot sector (for traditional BIOS/MBR systems) or the EFI partition (for more recent (Unified) Extensible Firmware Interface or EFI/UEFI systems). Up to this stage, the machine does not access any mass storage media. Thereafter, information on date, time, and the most important peripherals are loaded from the CMOS values (after a technology used for the battery-powered memory store which allows the system to keep track of the date and time even when it is powered off).

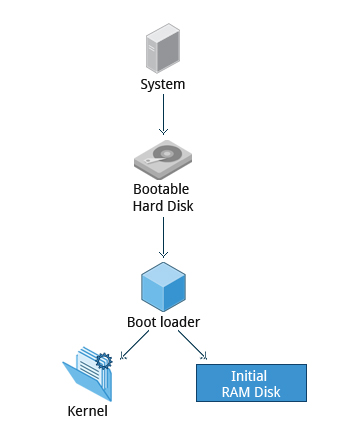

A number of boot loaders exist for Linux; the most common ones are GRUB (for GRand Unified Boot loader), ISOLINUX (for booting from removable media), and DAS U-Boot (for booting on embedded devices/appliances). Most Linux boot loaders can present a user interface for choosing alternative options for booting Linux, and even other operating systems that might be installed. When booting Linux, the boot loader is responsible for loading the kernel image and the initial RAM disk or filesystem (which contains some critical files and device drivers needed to start the system) into memory.

Boot Loader in Action

The boot loader has two distinct stages:

For systems using the BIOS/MBR method, the boot loader resides at the first sector of the hard disk, also known as the Master Boot Record (MBR). The size of the MBR is just 512 bytes. In this stage, the boot loader examines the partition table and finds a bootable partition. Once it finds a bootable partition, it then searches for the second stage boot loader, for example GRUB, and loads it into RAM (Random Access Memory). For systems using the EFI/UEFI method, UEFI firmware reads its Boot Manager data to determine which UEFI application is to be launched and from where (i.e. from which disk and partition the EFI partition can be found). The firmware then launches the UEFI application, for example GRUB, as defined in the boot entry in the firmware’s boot manager. This procedure is more complicated, but more versatile than the older MBR methods.

The second stage boot loader resides under /boot. A splash screen is displayed, which allows us to choose which operating system (OS) to boot. After choosing the OS, the boot loader loads the kernel of the selected operating system into RAM and passes control to it. Kernels are almost always compressed, so its first job is to uncompress itself. After this, it will check and analyze the system hardware and initialize any hardware device drivers built into the kernel.

Initial RAM Disk

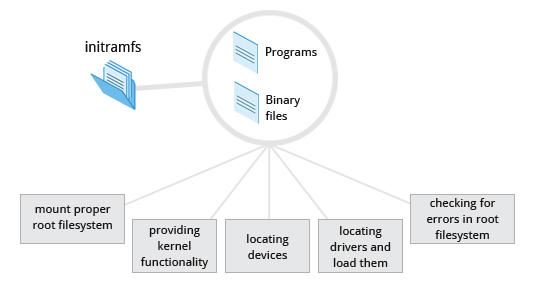

The initramfs filesystem image contains programs and binary files that perform all actions needed to mount the proper root filesystem, like providing kernel functionality for the needed filesystem and device drivers for mass storage controllers with a facility called udev (for user device), which is responsible for figuring out which devices are present, locating the device drivers they need to operate properly, and loading them. After the root filesystem has been found, it is checked for errors and mounted.

The mount program instructs the operating system that a filesystem is ready for use, and associates it with a particular point in the overall hierarchy of the filesystem (the mount point). If this is successful, the initramfs is cleared from RAM and the init program on the root filesystem (/sbin/init) is executed.

init handles the mounting and pivoting over to the final real root filesystem. If special hardware drivers are needed before the mass storage can be accessed, they must be in the initramfs image.

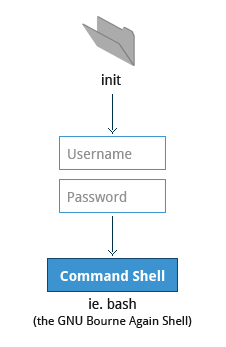

Text-Mode Login

Near the end of the boot process, init starts a number of text-mode login prompts. These enable you to type your username, followed by your password, and to eventually get a command shell. However, if you are running a system with a graphical login interface, you will not see these at first.

As you will learn in Chapter 7: Command Line Operations, the terminals which run the command shells can be accessed using the ALT key plus a function key. Most distributions start six text terminals and one graphics terminal starting with F1 or F2. Within a graphical environment, switching to a text console requires pressing CTRL-ALT + the appropriate function key (with F7 or F1 leading to the GUI).

Usually, the default command shell is bash (the GNU Bourne Again Shell), but there are a number of other advanced command shells available. The shell prints a text prompt, indicating it is ready to accept commands; after the user types the command and presses Enter, the command is executed, and another prompt is displayed after the command is done.

Kernel, init and Services

The Linux Kernel

Kernel is heart of Linux OS. It manages resource of Linux OS. Resources means facilities available in Linux. For e.g. Facility to store data, print data on printer, memory, file management etc .

Kernel decides who will use this resource, for how long and when. It runs your programs (or set up to execute binary files). The kernel acts as an intermediary between the computer hardware and various programs/application/shell.

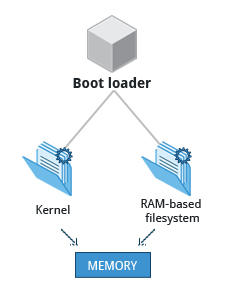

The boot loader loads both the kernel and an initial RAM–based file system (initramfs) into memory, so it can be used directly by the kernel.

When the kernel is loaded in RAM, it immediately initializes and configures the computer’s memory and also configures all the hardware attached to the system. This includes all processors, I/O subsystems, storage devices, etc. The kernel also loads some necessary user space applications.

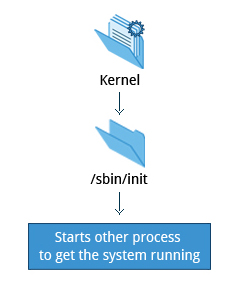

/sbin/init and Services

Once the kernel has set up all its hardware and mounted the root filesystem, the kernel runs /sbin/init. This then becomes the initial process, which then starts other processes to get the system running. Most other processes on the system trace their origin ultimately to init; exceptions include the so-called kernel processes. These are started by the kernel directly, and their job is to manage internal operating system details.

Besides starting the system, init is responsible for keeping the system running and for shutting it down cleanly. One of its responsibilities is to act when necessary as a manager for all non-kernel processes; it cleans up after them upon completion, and restarts user login services as needed when users log in and out, and does the same for other background system services.

Traditionally, this process startup was done using conventions that date back to the 1980s and the System V variety of UNIX. This serial process had the system passing through a sequence of runlevels containing collections of scripts that start and stop services. Each runlevel supported a different mode of running the system. Within each runlevel, individual services could be set to run, or to be shut down if running.

However, all major distributions have moved away from this sequential runlevel method of system initialization, although they usually emulate many System V utilities for compatibility purposes. Next, we discuss the new methods, of which systemd has become dominant.

Startup Alternatives

SysVinit viewed things as a serial process, divided into a series of sequential stages. Each stage required completion before the next could proceed. Thus, startup did not easily take advantage of the parallel processing that could be done on multiple processors or cores.

Furthermore, shutdown and reboot was seen as a relatively rare event; exactly how long it took was not considered important. This is no longer true, especially with mobile devices and embedded Linux systems. Some modern methods, such as the use of containers, can require almost instantaneous startup times. Thus, systems now require methods with faster and enhanced capabilities. Finally, the older methods required rather complicated startup scripts, which were difficult to keep universal across distribution versions, kernel versions, architectures, and types of systems. The two main alternatives developed were:

Upstart

- Developed by Ubuntu and first included in 2006

- Adopted in Fedora 9 (in 2008) and in RHEL 6 and its clones

systemd

- Adopted by Fedora first (in 2011)

- Adopted by RHEL 7 and SUSE

- Replaced Upstart in Ubuntu 16.04

While the migration to systemd was rather controversial, it has been adopted by all major distributions, and so we will not discuss the older System V method or Upstart, which has become a dead end. Regardless of how one feels about the controversies or the technical methods of systemd, almost universal adoption has made learning how to work on Linux systems simpler, as there are fewer differences among distributions. We enumerate systemd features next.

systemd Features

Systems with systemd start up faster than those with earlier init methods. This is largely because it replaces a serialized set of steps with aggressive parallelization techniques, which permits multiple services to be initiated simultaneously.

Complicated startup shell scripts are replaced with simpler configuration files, which enumerate what has to be done before a service is started, how to execute service startup, and what conditions the service should indicate have been accomplished when startup is finished. One thing to note is that /sbin/init now just points to /lib/systemd/systemd; i.e. systemd takes over the init process.

One systemd command (systemctl) is used for most basic tasks. While we have not yet talked about working at the command line, here is a brief listing of its use:

- Starting, stopping, restarting a service (using httpd, the Apache web server, as an example) on a currently running system:

$ sudo systemctl start|stop|restart httpd.service - Enabling or disabling a system service from starting up at system boot:

$ sudo systemctl enable|disable httpd.service

- Starting, stopping, restarting a service (using httpd, the Apache web server, as an example) on a currently running system:

In most cases, the .service can be omitted. There are many technical differences with older methods that lie beyond the scope of our discussion.

Linux Filesystems Basics

Think of a refrigerator that has multiple shelves that can be used for storing various items. These shelves help you organize the grocery items by shape, size, type, etc. The same concept applies to a filesystem, which is the embodiment of a method of storing and organizing arbitrary collections of data in a human-usable form.

Different types of filesystems supported by Linux:

- Conventional disk filesystems: ext3, ext4, XFS, Btrfs, JFS, NTFS, vfat, exfat, etc.

- Flash storage filesystems: ubifs, jffs2, yaffs, etc.

- Database filesystems

- Special purpose filesystems: procfs, sysfs, tmpfs, squashfs, debugfs, fuse, etc.

This section will describe the standard filesystem layout shared by most Linux distributions.

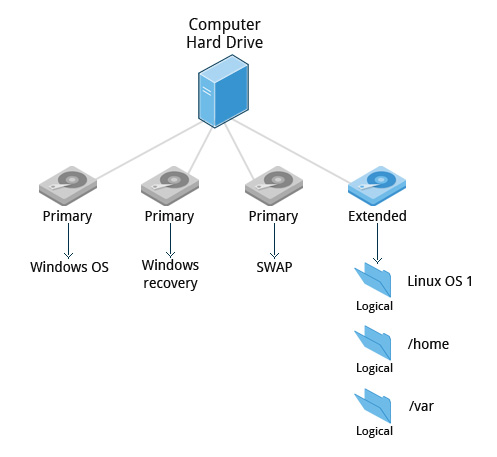

Partitions and Filesystems

A partition is a physically contiguous section of a disk, or what appears to be so in some advanced setups.

A filesystem is a method of storing/finding files on a hard disk (usually in a partition).

One can think of a partition as a container in which a filesystem resides, although in some circumstances, a filesystem can span more than one partition if one uses symbolic links, which we will discuss much later.

A comparison between filesystems in Windows and Linux is given in the accompanying table:

| Windows | Linux | |

| Partition | Disk1 | /dev/sda1 |

| Filesystem Type | NTFS/VFAT | EXT3/EXT4/XFS/BTRFS… |

| Mounting Parameters | DriveLetter | MountPoint |

| Base Folder (where OS is stored) | C:\ | / |

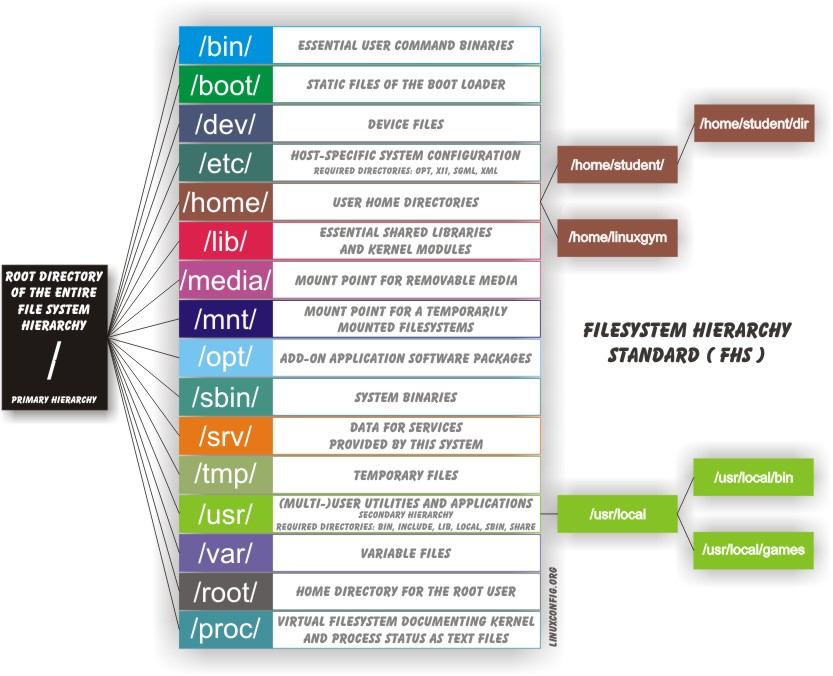

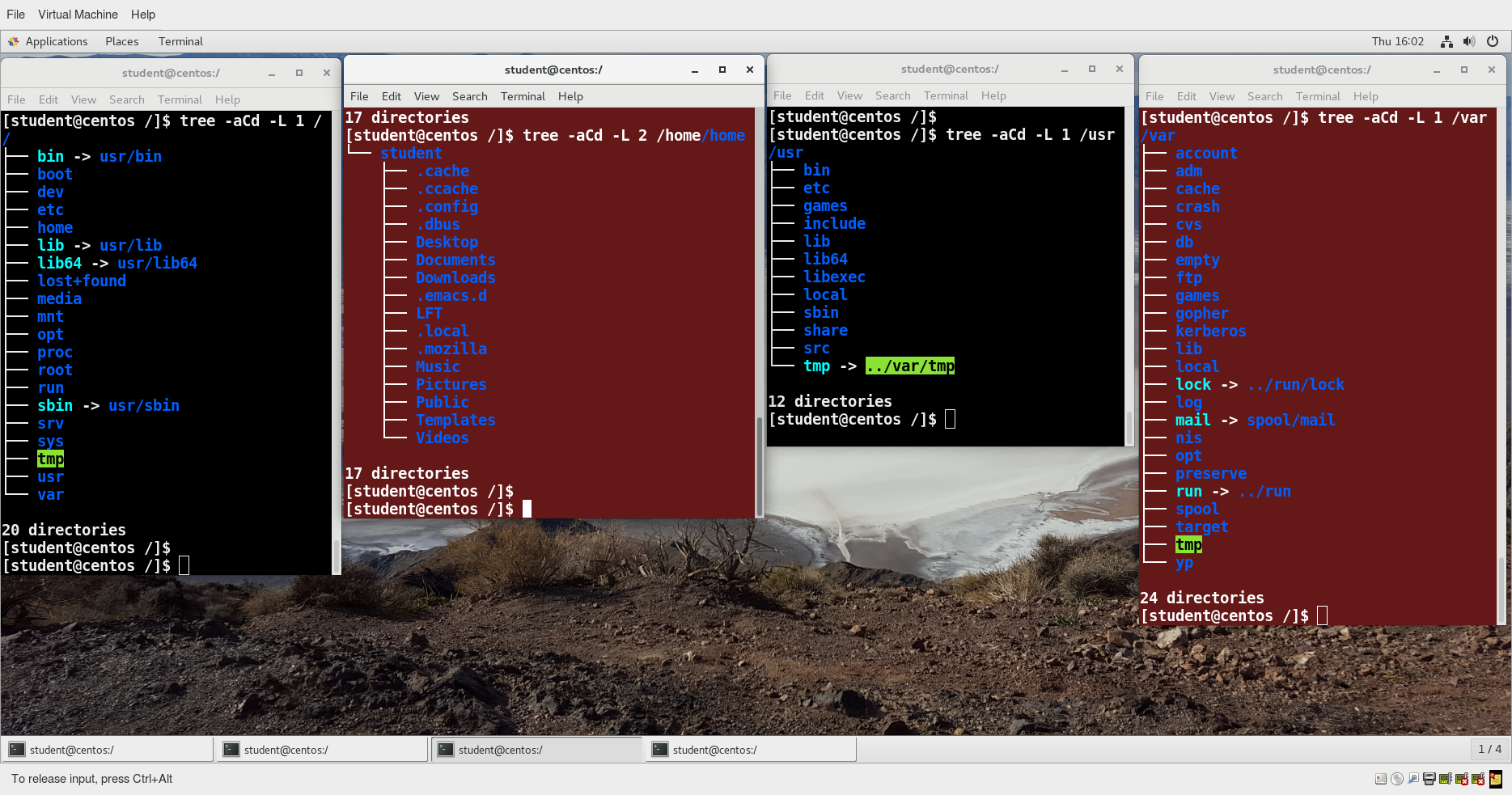

The Filesystem Hierarchy Standard

Linux systems store their important files according to a standard layout called the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS), which has long been maintained by the Linux Foundation. For more information, take a look at the following document: “Filesystem Hierarchy Standard“ created by LSB Workgroup. Having a standard is designed to ensure that users, administrators, and developers can move between distributions without having to re-learn how the system is organized.

Linux uses the ‘/’ character to separate paths (unlike Windows, which uses ‘\’), and does not have drive letters. Multiple drives and/or partitions are mounted as directories in the single filesystem. Removable media such as USB drives and CDs and DVDs will show up as mounted at /run/media/yourusername/disklabel for recent Linux systems, or under /media for older distributions. For example, if your username is student a USB pen drive labeled FEDORA might end up being found at /run/media/student/FEDORA, and a file README.txt on that disc would be at /run/media/student/FEDORA/README.txt.

More About the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard

All Linux filesystem names are case-sensitive, so /boot, /Boot, and /BOOT represent three different directories (or folders). Many distributions distinguish between core utilities needed for proper system operation and other programs, and place the latter in directories under /usr (think user). To get a sense for how the other programs are organized, find the /usr directory in the diagram from the previous page and compare the subdirectories with those that exist directly under the system root directory (/).

Linux Distribution Installation

Choosing a Linux Distribution

Suppose you intend to buy a new car. What factors do you need to consider to make a proper choice? Requirements which need to be taken into account include the size needed to fit your family in the vehicle, the type of engine and gas economy, your expected budget and available financing options, reliability record and after-sales services, etc.

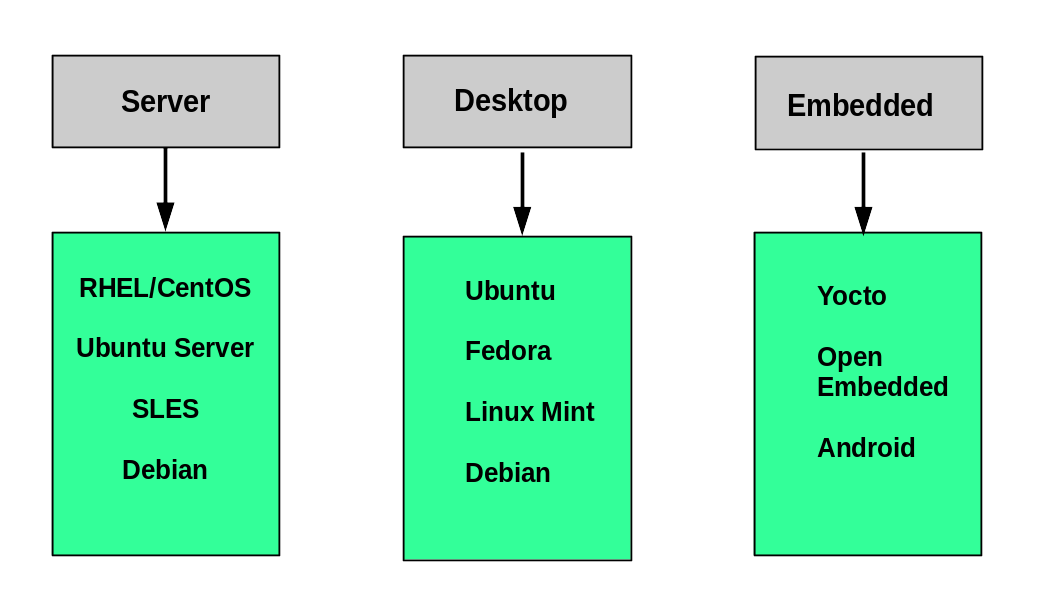

Similarly, determining which distribution to deploy also requires planning. The figure shows some, but not all choices. Note that many embedded Linux systems use custom crafted contents, rather than Android or Yocto.

Questions to Ask When Choosing a Distribution

Some questions worth thinking about before deciding on a distribution include:

- What is the main function of the system (server or desktop)?

- What types of packages are important to the organization? For example, web server, word processing, etc.

- How much hard disk space is required and how much is available? For example, when installing Linux on an embedded device, space is usually constrained.

- How often are packages updated?

- How long is the support cycle for each release? For example, LTS releases have long-term support.

- Do you need kernel customization from the vendor or a third party?

- What hardware are you running on? For example, it might be X86, ARM, PPC, etc.

- Do you need long-term stability? Can you accept (or need) a more volatile cutting edge system running the latest software?

Linux Installation: Planning

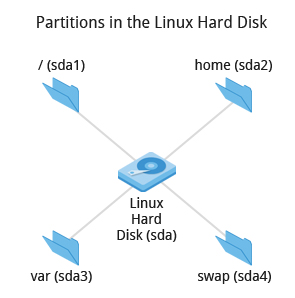

The partition layout needs to be decided at the time of installation; it can be difficult to change later. While Linux systems handle multiple partitions by mounting them at specific points in the filesystem, and you can always modify the design later, it is always easier to try and get it right to begin with.

Nearly all installers provide a reasonable default layout, with either all space dedicated to normal files on one big partition and a smaller swap partition, or with separate partitions for some space-sensitive areas like /home and /var. You may need to override the defaults and do something different if you have special needs, or if you want to use more than one disk.

Linux Installation: Software Choices

All installations include the bare minimum software for running a Linux distribution.

Most installers also provide options for adding categories of software. Common applications (such as the Firefox web browser and LibreOffice office suite), developer tools (like the vi and emacs text editors, which we will explore later in this course), and other popular services, (such as the Apache web server tools or MySQL database) are usually included. In addition, for any system with a graphical desktop, a chosen desktop (such as GNOME or KDE) is installed by default.

All installers set up some initial security features on the new system. One basic step consists of setting the password for the superuser (root) and setting up an initial user. In some cases (such as Ubuntu), only an initial user is set up; direct root login is not configured and root access requires logging in first as a normal user and then using sudo, as we will describe later. Some distributions will also install more advanced security frameworks, such as SELinux or AppArmor. For example, all Red Hat-based systems including Fedora and CentOS always use SELinux by default, and Ubuntu comes with AppArmor up and running.

Linux Installation: Install Source

Like other operating systems, Linux distributions are provided on removable media such as USB drives and CDs or DVDs. Most Linux distributions also support booting a small image and downloading the rest of the system over the network. These small images are usable on media, or as network boot images, in which case it is possible to perform an install without using any local media.

Many installers can do an installation completely automatically, using a configuration file to specify installation options. This file is called a Kickstart file for Red Hat-based systems, an AutoYAST profile for SUSE-based systems, and a Preseed file for Debian-based systems.

Each distribution provides its own documentation and tools for creating and managing these files.

Linux Installation: The Process

The actual installation process is pretty similar for all distributions.

After booting from the installation media, the installer starts and asks questions about how the system should be set up. These questions are skipped if an automatic installation file is provided. Then, the installation is performed.

Finally, the computer reboots into the newly-installed system. On some distributions, additional questions are asked after the system reboots.

Most installers have the option of downloading and installing updates as part of the installation process; this requires Internet access. Otherwise, the system uses its normal update mechanism to retrieve those updates after the installation is done.

NOTE: We will be demonstrating the installation process in each of the three Linux distribution families we cover in this course. You can view a demonstration for the distribution type of your choice.

Linux Installation: The Warning

IMPORTANT!

The demonstrations show how to install Linux directly on your machine, erasing everything that was there. While the demonstrations will not alter your computer, following these procedures in real life will erase all current data.

The Linux Foundation has a document: “Preparing Your Computer for Linux Training” (see below) that describes alternate methods of installing Linux without overwriting existing data. You may want to consult it, if you need to preserve the information on your hard disk.

These alternate methods are:

- Re-partitioning your hard disk to free up enough room to permit dual boot (side-by-side) installation of Linux, along with your present operating system.

- Using a host machine hypervisor program (such as VMWare’s products or Oracle Virtual Box) to install a client Linux Virtual Machine.

- Booting off of and using a Live CD or USB stick and not writing to the hard disk at all.

The first method is sometimes complicated and should be done when your confidence is high and you understand the steps involved. The second and third methods are quite safe and make it difficult to damage your system.

Please view the below YOUTUBE video for installing:

Ubuntu Linux

CentOS Linux

OpenSUSE Linux

Summary

Let’s summarize the key concepts covered:

- A partition is a logical part of the disk.

- A filesystem is a method of storing/finding files on a hard disk.

- By dividing the hard disk into partitions, data can be grouped and separated as needed. When a failure or mistake occurs, only the data in the affected partition will be damaged, while the data on the other partitions will likely survive.

- The boot process has multiple steps, starting with BIOS, which triggers the boot loader to start up the Linux kernel. From there, the initramfs filesystem is invoked, which triggers the init program to complete the startup process.

- Determining the appropriate distribution to deploy requires that you match your specific system needs to the capabilities of the different distributions.